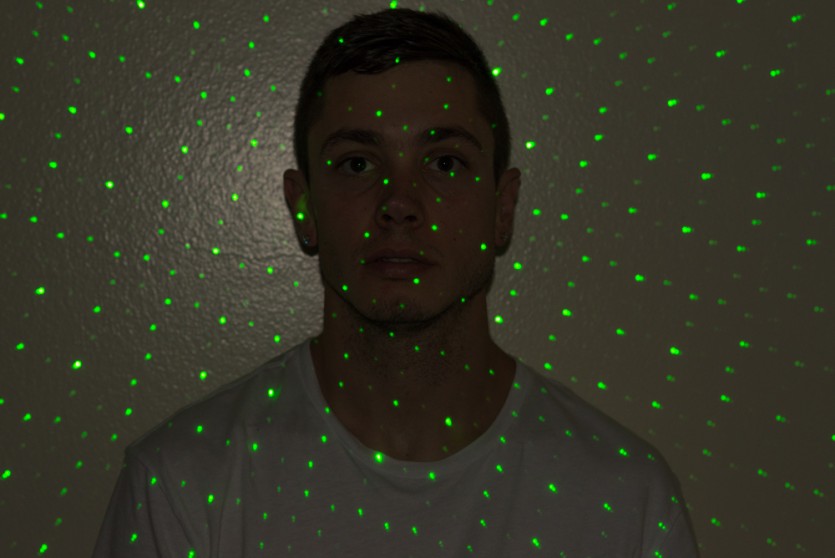

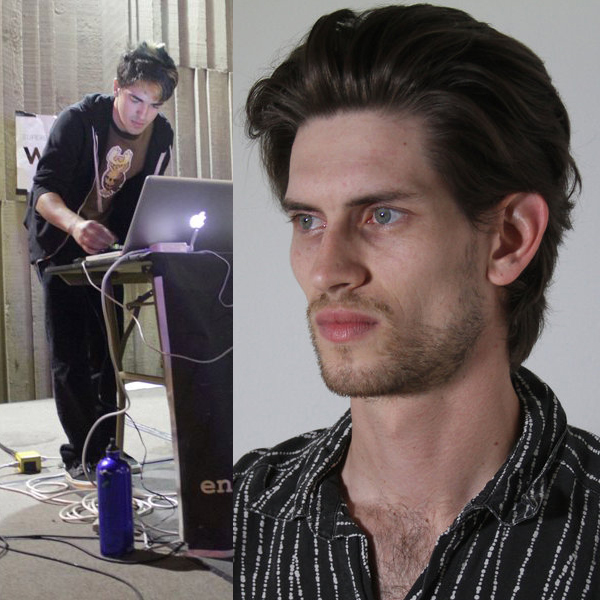

Over the last two years, MIZU has collaborated with Rachika Nayar and contributed to Maria BC’s celebrated Spike Field. She has ventured into theater and performance art, working with movement artists and costume designers in collaborative live performances, staging stunning shows at Pioneer Works directed by George Miller and at the Spring Hill Arts Gathering with members of The Here and There Collective. She has leapt surefootedly from life as a Juilliard-trained cellist into her role as a shimmering light in the world of contemporary experimental music. Her first record, Distant Intervals, received enthusiastic critical praise. Writing for Bandcamp, Vanessa Ague says that MIZU “captures both the turbulence and the euphoria of transformational times.” And on Forest Scenes, MIZU pushes the experiment, and the transformation, further.

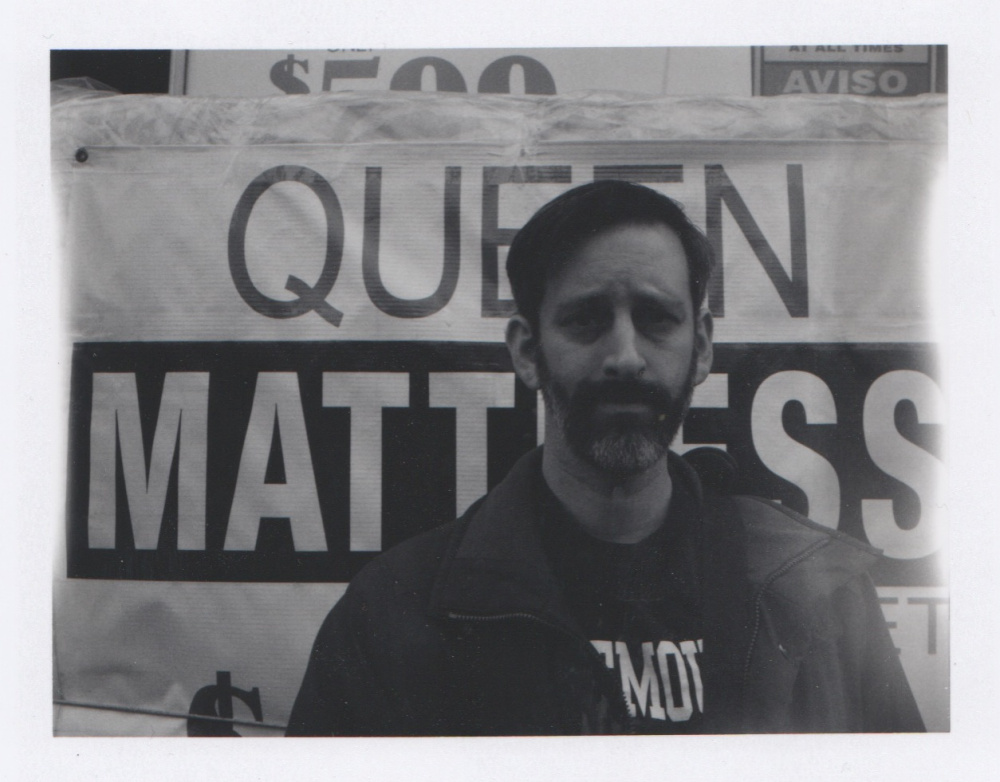

Proceeding from Robert Schumann’s Waldszenen in name and, to some extent, concept, MIZU began work on Forest Scenes immediately after completing Distant Intervals (recording then as Issei Herr), conceiving and writing the record over the course of two inspired weeks in São Paulo, Brazil in Summer 2022 and completing it over the following year in New York. While Distant Intervals engaged and inverted the classical idioms in which MIZU was reared, Forest Scenes lunges even further away from that world. It is in no small way an acknowledgement of transcendent experiences and the thrills of self-discovery, whether in the vast urbanity of São Paulo, in community among New York City’s queer spaces and dancefloors, or in the more abstract place of a self in transition. Pulling from these energies, MIZU loops in techno producer Concrete Husband, who features on “prphtbrd,” to further ornament the dancefloor flirtations.

While MIZU was socially transitioning during the creation of Distant Intervals, she began a physical gender transition in step with the inception of Forest Scenes. The record parallels this transformation, interrogating the boundaries between the forest and what is before / beyond it, building scenes of self-discovery through a kind of ecstasy in the unexplored. The forest is, at least in part, a metaphor for queer spaces, for spaces of self-discovery through community, through encounter. But the spaces of self-discovery, for MIZU, are also very much found within the songs themselves. This marvelous symbolic complexity holds Forest Scenes aloft, above mundane considerations of what is more or less beautiful. What is pastoral, what is modern, what is natural; all these considerations are teased out by MIZU’s compelling production, as she weaves electronic and environmental sounds, and cello both heavily processed and laid bare in a glorious, sweeping dream that will certainly appeal to fans of William Basinski or Tim Hecker. But the headlong dives into deconstructionist experimentation resonate like Arca or Marina Herlop and the pathos, vulnerability, and staggering range of densities through a single instrumental body may call to mind the emphatic focus of Hatis Noit. But however this music may resonate with fans of MIZU’s contemporaries, Forest Scenes could not be more her own, as she discovers herself within it.